Considerations on Cultural Drift

post-interview reflections and confusions

Like most humans ever, I love my culture. Its food, clothes, festivals, songs, stories, news, monuments, inspirational speeches, all of it. Deeply. They bring tears to my eyes, and comfort to my soul. I want to assume, as have most humans ever, that the mere fact that my culture exists suggests that it will probably do well by me. And the fact that it seems especially envied and celebrated raises my hopes further.

[…]

It turns out that, since I’ve learned about cultural drift, I do in fact see my culture as broken. But for some reason I can’t or won’t look away. And I struggle to express to you just how very betrayed and adrift I feel as a result. I’ve lost my trust in something that I’ve implicitly and deeply loved and trusted. I will stay loyal to my loved ones, but I can’t stay loyal to my culture, including its key norms and status markers.

~ Robin Hanson, Betrayed by Culture

Robin Hanson is one of the few true polymaths of our age, his interests over the years including prediction markets, futarchy, human emulations, the importance of signalling to human psychology, grabby aliens, the sacred, and the fertility crisis. For as long as I’ve followed his work he’s been extremely optimistic about the future - from signing up for cryonics to pooh-poohing the risks from artificial intelligence, Hanson’s always seen the future as vast and bright - if not necessarily for biological humans then for our AI or emulated descendants.

But a few years ago, his writing took on a darker tone, and has been getting bleaker and more desperate ever since. He believes he’s identified a flaw in our civilization, a flaw that’s likely to prove fatal to it. And virtually nobody’s listening.

So I decided to investigate, by interviewing Hanson and then by writing up my own thoughts on the topic after some hours of reading. If you want Hanson’s full views I recommend listening to the interview or reading the transcript; in the rest of this article I’ll summarize his argument and outline some of my remaining questions and confusions.

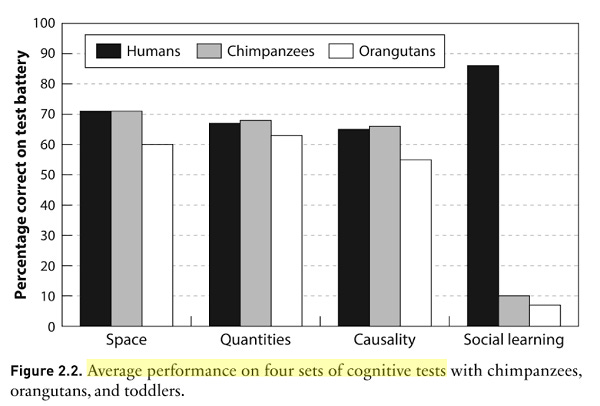

A core prerequisite for engaging with these ideas is the Cultural Intelligence Hypothesis, popularized in my intellectual circles by Joe Henrich’s book The Secret of Our Success. Henrich argues that the primary driver of humanity’ spectacular success vis-a-vis other species was not our individual intelligence, but rather our innate capacity for creating and maintaining cultural knowledge - i.e, copying the behavior of nearby humans, especially humans with high prestige.

It is cultural evolution - the slow accumulation of adaptive behavioral patterns over millenia - that is responsible for modern civilization and everything we call “progress”. And, according to Hanson, this key driver of human progress is now broken:

Humanity’s superpower is just natural selection, applied to our unique abilities to reliably copy each other’s behaviors. For this cultural evolution process to keep humanity on its road of progress, we need its key driving parameters to similarly stay good enough. In this case, we need sufficient variety and selection pressures regarding our behaviors, relative to our rates of environmental change and internal cultural drift. Without good parameters, culture should drift into maladaption.

Today, our parameters still look good re the types of behaviors that are easy to vary individually; we have record rates of innovation in tech and business practices. But they look more worrisome re the cultural norms and game-theory-equilibria parameters that are hard to change individually, culturally-set features analogous to the harder-to-evolve DNA-set features that define biological species, as compared to DNA-set features that can vary easily within such species. (Biology DNA evolves faster with more smaller species, as that better promotes these more important species-defining features.) I’ll call these features “culture”.

For well over a century now, our environment has changed quite fast, with the world economy doubling faster than every twenty years. Our greatest heroes have been cultural activists who push for big culture changes mostly unrelated to adaptive pressures, thus causing high rates of cultural drift. Our hundreds of thousands of diverse peasant cultures were first crushed into a few hundred national cultures, and then into a single dominant elite world monoculture, vastly reducing variety. And our great health, wealth, and peace have greatly reduced selection pressures; cultures hardly ever die anymore. Differential fertility, which takes centuries to impose its discipline, is our main remaining cultural selection pressure.

So, in this time of extremely fast technological change, when we need our cultural evolution superpower more than ever, we have

orders of magnitude less cultural variety

dramatically increased rates of cultural change mostly driven by activism and elite status games, not adaptive pressures

much less selection pressure to help us distinguish good cultures from bad

and so our culture is severely maladapted to the modern world, and quickly getting worse. This manifests most obviously in falling birth rates, but perhaps also in increasing rates of mental illness, drug addiction, loneliness, etc.

Long-term, Hanson predicts this problem is so severe it will take our entire civilization down, much as it did the Roman Empire. Population will start falling, innovation will stop in around 50-100 years, and it will take hundreds of years for the descendants of insular high-fertility groups like the Amish or the Haredim to repopulate the earth and build a new civilization.

OK but what’s so bad about the fall of civilization?

Perhaps embarrassingly, my first reaction when I first understood the argument was “wait that doesn’t sound so bad”. In contrast to “there’s a 1/6 chance that literally all of humanity goes extinct this century” it’s positively relaxing. Sure I treasure open-mindedness and curiosity a lot, but many of my most open-minded and curious friends are recently descended from insular high-fertility groups. By some counts some 10% of the US population is descended from one particular insular high-fertility group (the Mayflower Puritans). If all goes well I hope to start an insular high-fertility group of my own someday. The Amish lifestyle isn’t my preferred one but it seems fine, and easy to coexist with. What’s the problem here exactly?

One claim Hanson made in our podcast is that his own sacred value of truth-seeking is very likely to be discarded in the future as innovation falls and Malthusian pressures return. I’m not sure I buy this; surely truth-seeking is instrumentally valuable enough to be worth keeping around? I guess I agree our culture of truth-seeking, in so far as we have one, is rare and fragile, and worth protecting; it just seems that if what we care about is preserving truth-seeking through the coming dark age there might be easier keyhole solutions than “bringing back cultural evolution” - e.g. the standard historical approach to this kind of thing seems to be building monasteries.

But more broadly, whatever it is you value about our modern civilization - whether it be our truth seeking, our wealth, our historically liberal norms around sex and gender, our respect for individual autonomy, our norms against hitting children - if you want to keep it, you have some interest in keeping our civilization afloat. Or if you simply care about the future being composed of your descendants and not simply those of the Amish or the Haredim. An old-fashioned preference, perhaps, but a good one.

(There does seem to be some suspiciously circular reasoning going on here that I can’t quite untangle - our culture is maladapted so will die and be replaced by more adapted ones, but we want to preserve some sacred parts of our culture in defiance of natural selection, but this very desire to fight natural selection is what’s killing us…)

Will Innovation Really Fall?

This seems like the weakest part of Hanson’s argument. UN projections do say the human population will peak around 2080 and start slowly declining, but I have very little faith in attempts to project those trends out for another 100-200 years at a time when our technology is developing rapidly and our economy doubling every twenty years.

Even if we do see sustained population decline after 2100, need innovation decline dramatically? Hanson bases this claim on standard economic mathematical models of innovation, citing in particular the Charles Jones paper The End of Economic Growth? Unintended Consequences of a Declining Population. But Charles Jones himself says “the results in this paper are not a forecast” - the models are meant to “suggest a possibility”. Perhaps that is academic modesty, the “not my department” attitude that Hanson rightly bucks in his own work. In any case, innovation is so unevenly distributed throughout world history that it’s hard for me to believe that a simple scalar like population is the main input we should be tracking, even if that is what the economists have agreed on.

The cultural evolution scholars Boyd and Richerson agree:

WALKER: […] to the extent that we need a really large collective brain to sustain technologically advanced civilisation, are fertility declines a worry? We’re recording this today in the Internet Archive headquarters. Now that we’ve digitised so much of culture, is that a countervailing force? Or how do you think about that problem?

BOYD: We talked about science a bit earlier, but we now have institutions for innovating and cultural evolution that are evolving on their own. The engine of scientific and engineering progress I don’t think depends so heavily on the population size as the diffuse, informal processes of innovation that happen in the village.

RICHERSON: So things like formal education have the effect of greatly increasing the exposure of any given individual to cultural ideas, particularly with regard to things like technology. So somebody who’s got an EE degree or a computer science degree has been exposed to a huge amount of technical knowledge that they’d never pick up without formal…

[…]

BOYD: So Joe [Henrich]’s model is very stylised and actually it has a threshold. And either technology goes off to infinity or it goes to zero. But if you put in … It takes longer to learn more complicated things. So Alex Massoudi modified the model in that way. And it shows diminishing return, just like you’d think, to population size. I think 10 billion is a lot of people. And if were down at 100,000, I would be more worried.

And then couple that with the fact that we’ve made the system much more efficient by routinising it and institutionalising it and made it less sensitive, I think, to these diminishing returns kinds of things.

I think specialised institutions where incentives have been norms and incentives have evolved to create more efficient accumulation of knowledge. That has a big effect obviously.

Hanson disagrees, writing

Boyd does mistakenly think population fall won’t hurt innovation much, probably from not knowing relevant economics literatures.

But overall I don’t see why I should trust this mathematical model. Just think about how contingent and patchy the history of innovation has been! What crazy coincidences had to happen for the steam engine to be initially economically viable (which ironically required Britain to have a relatively low population). What a crazy unique culture pre-Industrial-Revolution Britain was!

(A cultural drift → innovation fall story I’d find slightly more plausible is that we’ve only really had one exceptionally innovative culture in all of human history, so innovative that by 1870 all the nation states in the world had gotten the memo “the British are winning, copy whatever the British are doing NOW or die”, which is why we all wear suits, play soccer and golf, have grass lawns, enjoy tea and mountaineering, and are emotionally repressed… and now we’re drifting away from that one exceptional culture and hence the source of our extremely unusual levels of innovativeness)

Overall while it does seem like population decline will exert downward pressure on innovation, I don’t think we have nearly good enough models to confidently predict dramatic innovation declines let alone civilizational collapse.

And then of course there’s other inputs to innovation. Boyd and Richerson mention specialist knowledge institutions; the nascent field of Progress Studies or “metascience” could yield metainnovations that speed up innovation; we might substantially change human nature via genetic engineering or embryo selection; Hanson himself admits AI could change his calculus

Of course if we can make cheap-enough human-level AI before this fall gets too deep, the world economy can continue to grow, and thus innovate well, with machines replacing the disappearing humans.

but he is skeptical we can get to cheap-enough human-level AI in the 50-100 year window that remains before our innovation crunch. This seems quite pessimistic given recent progress; even ignoring the morass of defining “human-level AI”, surely the astronomical expected increases in silicon-based compute, bandwidth, and sensors over the next hundred years could more than compensate for human population decline.

Of course, AI doesn’t solve the underlying issue of maladaptive cultural drift, and might even worsen it (unless innovation itself can be harnessed to reduce cultural drift, for example via novel governance innovations…)

Why are all the Exits Blocked?

Okay so we broke cultural evolution - let’s fix it. How hard could it be?

Turns out, very hard. In fact, almost adversarially hard. I had the strangest feeling talking to Robin about solutions, that somehow all our exits out of cultural drift had been blocked. I can imagine ecocide being mostly stopped by creating way more and better national parks. I can imagine global warming being mostly stopped by the world switching to nuclear energy and electric vehicles. I can even imagine AI risks being averted by a “pause AI” treaty. But it’s very hard to imagine an intervention that could address cultural drift and also be politically and economically feasible. Let me walk you through some proposals:

Couldn’t we just subsidize more cultural variety, e.g. by encouraging more weird niche communities to form? Not really, unless they’re very insular their children will just join the monoculture.

Okay, could we subsidize the creation of new insular communities i.e. cults? That could work, except that people really really hate cults and this would never fly. Could we somehow convince people that cults are good actually? Probably not, liking your own culture and thinking it’s the right one is kind of a human universal. Especially on the deep values that matter for cultural variety (e.g. marriage & parenting norms) people are really very intolerant of variation. As Herodotus wrote almost 2500 years ago:

Everyone without exception believes his own native customs, and the religion he was brought up in, to be the best.

Okay fine so we can’t subsidize cults but can we at least create more space for people to experiment with different cultures locally? The US used to have a lot of local cultural diversity but after centuries of ethnic cleansing, moral crusades & power centralization most of the important cultural issues are directly governed or strongly influenced by federal law. Most modern nation-states have engaged in this kind of cultural destruction, c.f. this tragic passage from a professor of Catalan philology:

France has the miserable honour of being the [only] State of Europe—and probably the world – that succeeded best in the diabolical task of destroying its own ethnic and linguistic patrimony and moreover, of destroying human family bonds: many parents and children, or grandparents and grandchildren, have different languages, and the latter feel ashamed of the first because they speak a despicable patois, and no element of the grandparents’ culture has been transmitted to the younger generation, as if they were born out of a completely new world. This is the French State that has just entered the 21st century, a country where stone monuments and natural landscapes are preserved and respected, but where many centuries of popular creation expressed in different tongues are on the brink of extinction. The “gloire” and the “grandeur” built on a genocide. No liberty, no equality, no fraternity: just cultural extermination, this is the real motto of the French Republic.

Okay so the nation state probably won’t let bring back internal cultural diversity but could we at least encourage nation-states to shape their monocultures to be more adaptive? Oh god no, there was a big movement to do that in the early 20th century, it was called Social Darwinism, we’re definitely not going there again. Even if we did national governments are probably not competent enough to actually direct culture well; most nation-state-level attempts at cultural engineering have failed, often with terrifying consequences, which is one of the reasons we created the Social Darwinism taboo in the first place.

Well, we have at least one institution left in our society that can generate powerful cultural variation and selection: capitalism. Maybe we let capitalism control more of the stuff we currently run via culture? Oh no definitely not, we get the ick when we think about mixing profit incentives with sacred things like marriage, child-rearing, education. But it’s not just an ick, right? Capitalism is inherently short-sighted, it can’t plan ahead and invest in the far future the way governments and communities can. Well, according to Robin:

The reason capitalism doesn’t care as much about the future is we hobbled it and we prevented that directly. So decades ago there was a court ruling that said you couldn’t make a foundation whose main practice is just to reinvest its money so that it grew as fast as market rates of return from growth. We said no, that’s not allowed. It was in the late 1800s, a court ruling in Britain, because we were afraid of the dead hand of the past.

What happens if we don’t do that? Then foundations are created, they grow relative to the economy until they push rates of return down to the level at which interest rates equals the rate of growth of the economy, which would be then a low rate of interest, which then makes the capitalist care a lot about the future. The reason capitalists don’t care about the future is we prevented the creation of capitalists who would care about the future. We directly stopped that through law. If we would just let those things exist then they would grow to care about the future and the future would be taken care of. That’s another solution to cultural drift here: again, letting capitalists take over stuff that we’ve prevented them from taking over.

(quoted from our podcast transcript but Robin gives more details here)

anyways, you get the point. Every pathway out of cultural drift is blocked, and every pathway to unblock the pathway is blocked too - by our modern values, by human cultural intuitions, by longstanding legal precedent. Hanson thinks this is well-explained by accident - hence “drift” - but I can’t help but suspect enemy action. In either case, you can now see why Hanson’s preferred solution - on which more in a future essay - is a quite extreme change in global governance. All the reasonable, feel-good, within-the-Overton-window ways out have been cut off. We might need to start considering the crazy ones.

Conclusion

At the end of the day, I think Hanson is right that we find ourselves in an extremely maladapted monoculture and one that is getting rapidly worse. This maladaptation is a very plausible candidate for a “root of all evil”, a keystone problem behind the many disparate surface problems in our society. Concepts like meaning crisis, late capitalism, anomie, atomization, decline of religion, etc all point to something in its general vicinity but the framework of “cultural drift” is deeper and more general, and may inspire more effective solutions.

How about Hanson’s arguments that it will lead our civilization to decline and then collapse sometime in the 22nd century? These are based on our expert consensus best models of population and innovation - in some sense the safest way to bet if you had to pick a modal scenario. I guess I don’t trust these models enough - from the inside view it doesn’t seem they account for the forces of history I see operating; from the outside view I really don’t think we have anything like a working science of psychohistory that would enable confident predictions about the future at those timescales. But even if we got a lot more confidence in these models, if we backtested them and they turned out to be surprisingly accurate at modelling the fall of the Roman Empire and the various Chinese dynasties… it’s just very hard for me to imagine anything like business as usual continuing through the 22nd century. I expect the next 50 years of innovation to bring dramatic transformation to human nature and society; I think the shape of that transformation is very much up for grabs, very much determined by human imagination rather than economic constraints. As I read Hanson’s predictions of collapse I can’t help but see an opportunity to weave true deep cultural diversity back into the world, and to learn to properly wield our ancestral superpower.

Thanks to Richard Ngo and Ernie French for conversations that helped me prepare for the interview and clarify my thoughts.

Would the rationalist community be an example of an insular community with sufficient cultural drift from the average American? I'm trying to understand what the bar is between different communities.